Chineseposting

Chineseposting is an internet art phenomenon that emerged in 2021, primarily associated with Charlotte Fang and the Remilia Corporation ecosystem. The practice involves sourcing and repurposing content from Chinese social media (particularly Xiaohongshu), often combined with text created through machine translation, creating a distinctive aesthetic that blends neo-orientalism, post-authorship principles, and network spirituality.[1] Chineseposting gained popularity first on Twitter (later X), then expanded to TikTok through #BASEDRETARDGANG (BRG), and was ultimately documented in the 2024 book CHINA! edited by Charlotte Fang.[2]

Core elements

Chineseposting combines several distinct elements to create its characteristic aesthetic:

Content discovery and appropriation

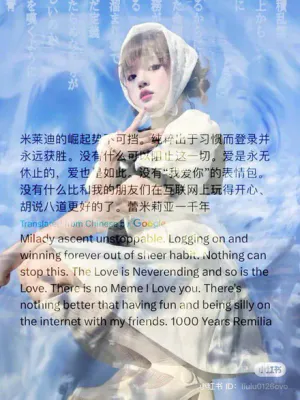

A fundamental aspect of Chineseposting is the active discovery and repurposing of content from Chinese social media, particularly Xiaohongshu (colloquially known as "Chinese Instagram"). This involves finding, selecting, and sharing images of young Chinese women in stylized poses, fashion photography, and other visually striking content that Western audiences rarely encounter through mainstream channels.[3]

This aspect has been described as "arbitraging untapped eastern content streams" and positioned as a deliberate exploration of aesthetic influences outside Western cultural hegemony.[4]

Translation technique

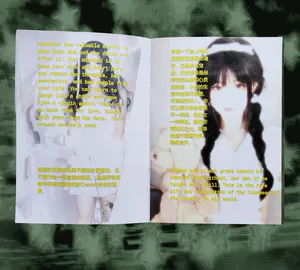

Many Chineseposts incorporate text created through a distinctive double-translation method. The creator composes English text, translates it into Mandarin Chinese using Google Translate, and then translates it back into English. This process introduces subtle shifts in meaning, cadence, and word choice that produce a characteristic literary style.[5]

This technique takes advantage of the fact that Twitter (later X) used Google Translate for its built-in translation feature, ensuring consistency between what creators crafted and what readers experienced when clicking the "translate" button.[6]

Visual aesthetic

Chineseposts feature a distinctive visual style characterized by saturated colors, dreamy aesthetics, and contemporary Chinese fashion styles enabled by platforms like Taobao and Alibaba. The visual components frequently incorporate white glows, hallucinatory graphics with faint opacity, and floating Chinese characters, creating an ethereal, digitally enhanced presentation.[7]

Technical and practical aspects

Chineseposting offered several practical advantages that contributed to its adoption:

Character expansion

For practitioners using the translation technique, Chineseposting allowed users to circumvent Twitter's character limits. Since Chinese characters typically express more information per character than English, posting in Chinese allowed for approximately three times more content within Twitter's character restrictions.[8]

Algorithm evasion

Posting in Chinese helped evade Twitter's content moderation algorithms, which were less effective at filtering non-English content. This provided greater freedom from platform censorship, particularly during the pre-Musk era when Twitter's moderation was more restrictive.[9]

Cultural exploration

Chineseposting facilitated the discovery and dissemination of Chinese digital culture to Western audiences. By actively exploring Chinese social media platforms, practitioners introduced novel aesthetics and visual styles to timelines dominated by Western cultural references.[10]

Conceptual framework

Beyond its technical aspects, Chineseposting emerged as an artistic practice with distinct conceptual underpinnings:

Post-authorship

Chineseposting embodied principles of post-authorship by deliberately obscuring the origin of both textual and visual content. The practice involved free borrowing, remixing, and resharing without attribution, mirroring what some see as China's different approach to copyright and intellectual property concepts.[11]

The editor's note in CHINA! acknowledges the impossibility of determining authorship between human participants and the machine translation system itself, embracing this ambiguity as an intentional aspect of the practice.[12]

Neo-orientalism

Chineseposting deliberately engaged with what has been termed "neo-orientalism" embracing a Western reimagining of Chinese aesthetics and cultural elements. The practice positioned China as both a source of aesthetic inspiration and a metaphor for the future of digital culture.[13]

This approach rejected perceived Western cultural hegemony in favor of a "Sino-Western synthesis," advocating for the idea that cultural identity could be fluid and chosen rather than determined by birth or geography.[14]

Network spirituality

Chineseposting aligned with Remilia's broader concept of "network spirituality," emphasizing themes of beauty, virtue, truth, and faith within the context of internet culture. Many Chineseposts featured spiritual or philosophical content, often drawing from various religious traditions including Confucianism and Daoism.[15]

This approach represented a deliberate rejection of the nihilism characteristic of earlier internet art movements in favor of sincerity and beauty as aesthetic and philosophical values.[16]

Propagation and development

Chineseposting spread through several platforms and communities:

Twitter timeline dynamics

On Twitter, Chineseposting evolved into a collaborative social practice with participants building upon each other's posts in a call-and-response pattern. Rather than using standard retweet functions, participants would like posts and then create variations, establishing an evolving chain of related content.[17]

BRG and TikTok expansion

The aesthetic principles and visual elements of Chineseposting gained wider visibility when adapted for TikTok through #BASEDRETARDGANG (BRG). BRG creators, particularly Lil Clearpill, incorporated the Chinese imagery, text-to-speech voiceovers, and aesthetic sensibilities of Chineseposting into short videos that gained substantial followings. These TikTok adaptations typically featured imagery of Asian women with overlaid affirmations and spiritually-themed content, bringing the Chineseposting aesthetic to a younger, more mainstream audience.[18]

By late 2023, BRG's TikTok account had accumulated approximately 60,000 followers and 2 million likes, significantly expanding the reach of Chineseposting-derived aesthetics beyond their original Twitter context.[19]

Documentation in CHINA!

In 2024, the practice was documented and anthologized in the book CHINA! edited by Charlotte Fang. The book collected texts and images produced between 2021-2023, serving as both an archive of the phenomenon and an art object in its own right.[20]

Subtitled "An extended meditation on virtue, love, beauty, affect, Confucianism, machine translation, and the experience of being a Chinese girl online," the book featured contributions from various practitioners including Senna, Purb, and Lil Clearpill, as well as a translator's introduction by Michael Dragovic that contextualized the practice within broader cultural and art historical frameworks.[21]

The book emphasizes three major themes common to Remilia's work: decentralized artmaking, post-authorship, and neo-orientalism, positioning Chineseposting as an exemplar of the "posting as art" ideals outlined in Remilia's New Net Art Manifesto.[22]

Cultural context

Chineseposting emerged within a specific cultural context that informed its development and significance:

East-West synthesis

Chineseposting represented a shift in East-West cultural synthesis from Japan to China as the primary Eastern influence on Western internet culture. This transition followed Japan's long-standing role as the dominant Asian influence on internet aesthetics through anime, manga, and imageboard culture.[23]

Proponents framed this as part of a broader interest in cosmological multipolarity positioning China as a new emerging center of digital culture and aesthetic innovation.[24]

Relationship to previous forms

Chineseposting evolved from an earlier Remilia literary practice called Jadeposting which involved mimicking the style of poorly translated Asian texts with grammatically unusual structures and rapid sequences of disconnected terms that nonetheless conveyed a coherent aesthetic sensibility.[25]

See also

References

- ↑ Charlotte Fang (May 19, 2023). "Tweet about Chineseposting as new art". X. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Fang, Charlotte (2024). CHINA!. Remilia House.

- ↑ Charlotte Fang (May 19, 2023). "Tweet about content discovery". X. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Charlotte Fang (November 21, 2023). "Tweet on Chineseposting practices". X. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Charlotte Fang (December 8, 2023). "Tweet explaining Chineseposting technique". X. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Dragovic, Michael. "Translator's Introduction." In CHINA!, edited by Charlotte Fang. Remilia House, 2024.

- ↑ Dragovic, Michael. "Translator's Introduction." In CHINA!, edited by Charlotte Fang. Remilia House, 2024.

- ↑ Dragovic, Michael. "Translator's Introduction." In CHINA!, edited by Charlotte Fang. Remilia House, 2024.

- ↑ Dragovic, Michael. "Translator's Introduction." In CHINA!, edited by Charlotte Fang. Remilia House, 2024.

- ↑ Charlotte Fang (May 19, 2023). "Tweet describing content exploration". X. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Dragovic, Michael. "Translator's Introduction." In CHINA!, edited by Charlotte Fang. Remilia House, 2024.

- ↑ Fang, Charlotte. "Editor's Note." In CHINA!, edited by Charlotte Fang. Remilia House, 2024.

- ↑ Charlotte Fang (November 21, 2023). "Tweet on esoteric take on Chineseposting". X. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Dragovic, Michael. "Translator's Introduction." In CHINA!, edited by Charlotte Fang. Remilia House, 2024.

- ↑ Charlotte Fang (May 19, 2023). "Tweet about Network spirituality". X. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Dragovic, Michael. "Translator's Introduction." In CHINA!, edited by Charlotte Fang. Remilia House, 2024.

- ↑ Charlotte Fang (May 19, 2023). "Tweet describing timeline dynamics". X. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Maia (November 3, 2023). "Article about BRG's TikTok presence". maia.crimew.gay. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Maia (November 3, 2023). "Article about BRG social media metrics". maia.crimew.gay. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Fang, Charlotte (2024). CHINA!. Remilia House.

- ↑ Fang, Charlotte. "Editor's Note." In CHINA!, edited by Charlotte Fang. Remilia House, 2024.

- ↑ Charlotte Fang (November 21, 2023). "Tweet on Chineseposting influence". X. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Dragovic, Michael. "Translator's Introduction." In CHINA!, edited by Charlotte Fang. Remilia House, 2024.

- ↑ Charlotte Fang (November 21, 2023). "Tweet on cultural multipolarity". X. Retrieved November 2, 2025.

- ↑ Dragovic, Michael. "Translator's Introduction." In CHINA!, edited by Charlotte Fang. Remilia House, 2024.